Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010)

excerpt from lyles, 2011, pp. 155-156

[remember, i wrote this in 2011, before Hobby Lobby in 2014]

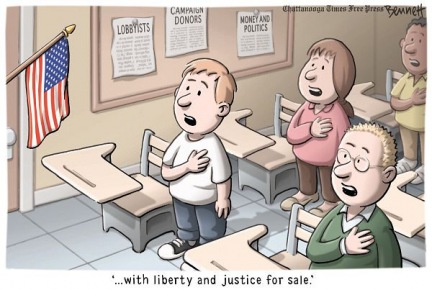

Citizens United removed most restrictions on corporate and union expenditures except for disclosure requirements. The Opinion of the Court provoked a strong dissent and also provoked much discussion off the Court. Opponents decried the opinion and claimed that it opened the floodgates for money to enter the political system, especially from corporations. They reject the claim that corporations have the same First Amendment rights as individuals. Moreover, they argue that there are compelling concerns about the integrity of elections that justify some speech regulation. Proponents argue that the case has finally removed untenable restrictions on corporate speech that cannot be squared with the First Amendment. Moreover, they claim that the decision allows more speech into the marketplace of ideas. They also point out that many powerful unions joined with corporations to oppose the law.

A particularly interesting example of the public discussion generated by this case occurred at President Obama’s 2010 State of the Union Address. Several Supreme Court Justices usually attend State of the Union speeches and are seated near the front. Despite very partisan responses from the members of Congress, the justices normally do not clap or show emotion that is related to substantive issues. The practice symbolizes their impartiality. Likewise, any criticism of the Supreme Court or one of its decisions is rare and usually indirect. For example, Presidents may criticize things such as “activist” judges, or implicitly criticize a rulingsuch as Roe v. Wade, but they rarely directly criticize the Supreme Court in that setting. President Obama, however, took brief but direct aim at Citizens United. In addition to stating a general criticism, he suggested that for the first time foreign corporations would now be free to try to influence American elections. Justice Samuel Alito was seen by television cameras as shaking his head and mouthing the words “not true.” The actual wording of the opinion does not resolve the disagreement between President Obama and Justice Alito. Much of the logic of the opinion would support the president’s reading, but the Court did not foreclose treating foreign corporations differently. Nevertheless, it was quite a moment.

The effects of Citizen United remain to be seen. Few doubt that it will increase the amount of money in politics. Whom that will favor is less predictable. Some argue that it is a slam-dunk victory for business interests. Though many unions supported the decision, given the declining strength of unions, most people see it as much more a victory for corporate interests. But corporate interests and business interests are not always the same. Some believe that corporations will use their power to seek regulations that will benefit them, often at the expense of small businesses. The opinion has left Congress greatly restrained on what it can regulate, but some believe that Congress could enhance disclosure requirements in ways that might discourage corporations from using their monetary muscle in areas that do not affect them directly. In any event, this case is an excellent reminder that law and politics are inevitably intertwined.

See also: http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/citizens-united-v-federal-election-commission/

- TITLE: Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

- FACTS: In January 2008, Citizens United, a conservative non-profit organization in the United States, released a 90 minute documentary entitled “Hillary: The Movie” which expressed opinions about whether Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton would make a good president. Citizens United distributed the movie in theaters and on DVD, but wanted to broadcast it on television and make it available through video-on-demand. In order to do so, Citizens United planned on using its general treasury funds. Under the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, corporations and unions are prohibited from spending their general treasury funds on “electioneering communications” or for speech that expressly advocates the election or defeat of a candidate. The Act defines an “electioneering communication” as any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication that (1) refers to a clearly identified candidate for federal office, (2) is made within 30 days of a primary election or 60 days of a general election, and (3) is publicly distributed. Citizens United sought an injunction against the Federal Election Commission in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia to prevent the application of the BCRA to its film. Citizens United argued that: 1) Section 203 violates the First Amendment on its face and when applied to their movie and its related advertisements, and that 2) Sections 201 and 203 are also unconstitutional as applied to the circumstances. The district court denied this motion and granted summary judgment to the FEC. Section 203 on its face was not unconstitutional because the Supreme Court in McConnell v. FEC had already reached that determination. The District Court also held that the movie was the functional equivalent of express advocacy, as it attempted to inform voters that Senator Clinton was unfit for office, and thus Section 203 was not unconstitutionally applied. Lastly, it held that Sections 201 and 203 were not unconstitutional as applied to the the movie or its advertisements. The court reasoned that the McConnell decision recognized that disclosure of donors “might be unconstitutional if it imposed an unconstitutional burden on the freedom to associate in support of a particular cause,” but those circumstances did not exist in Citizen United’s claim.

- ISSUES PRESENTED:

- Did the Supreme Court’s decision in McConnell resolve all constitutional as-applied challenges to the BCRA when it upheld the disclosure requirements of the statute as constitutional?

- Do the BCRA’s disclosure requirements impose an unconstitutional burden when applied to electioneering requirements because they are protected “political speech” and not subject to regulation as “campaign speech”?

- If a communication lacks a clear plea to vote for or against a particular candidate, is it subject to regulation under the BCRA?

- Should a feature length documentary about a candidate for political office be treated like the advertisements at issue in McConnell and therefore be subject to regulation under the BCRA?

- HOLDING: No. No. Yes. Yes. Reversed, in a 5-4 decision with an opinion written by Justice Kennedy. Justice Stevens dissented, joined by Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. Political spending is a form of protected speech under the First Amendment, and the government may not keep corporations or unions from spending money to support or denounce individual candidates in elections. While corporations or unions may not give money directly to campaigns, they may seek to persuade the voting public through other means, including ads, especially where these ads were not broadcast.

- REASONING: The majority maintained that political speech is indispensable to a democracy, which is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation. Justice Kennedy stated that “The First Amendment protects the resulting speech, even if it was enabled by economic transactions with persons or entities who disagree with the speaker’s ideas…No sufficient governmental interest justifies limits on political speech of nonprofit or for-profit corporations.” The First Amendment gives people the freedom to think for themselves, and by restricting corporate speech, the government silenced voices that best represent the most important segments of the economy. The majority also held that the BCRA’s disclosure requirements as applied to The Movie were constitutional, reasoning that disclosure is justified by a “governmental interest” in providing the “electorate with information” about election-related spending resources. The Court also upheld the disclosure requirements for political advertising sponsors and it upheld the ban on direct contributions to candidates from corporations and unions.

- CONCURRING/DISSENTING OPINION: In a separate concurring opinion, Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justice Alito, emphasized the care with which the Court handles constitutional issues and its attempts to avoid constitutional issues when at all possible. Here, the Court had no narrower grounds upon which to rule, except to handle the First Amendment issues embodied within the case. Justice Scalia also wrote a separate concurring opinion, joined by Justices Alito and Thomas in part, criticizing Justice Stevens’ understanding of the Framer’s view towards corporations. Justice Stevens argued that corporations are not members of society and that there are compelling governmental interests to curb corporations’ ability to spend money during local and national elections.

Recent Comments