Freshly Painted White Walls

This is an old blog post I wrote about my experiences as the first Black family on a previously all-white block in Chicago during the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

I have reposted it here [below] for your analysis/comment.

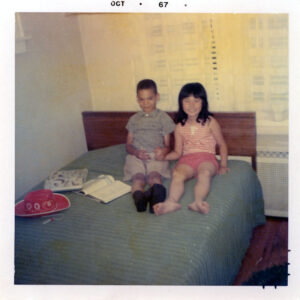

PolS 353. At the very end of class (Korematsu), I mentioned that my best friend when I was growing up was a little girl named Leslie Yokoyama. Although I did not know it at the time, when we connected decades later on Facebook, she told me about her parents and grandparents being in an internment camp during WW2. After the war, they did not return to CA, so they moved to Chicago, where Leslie was born. Leslie now lives in Northen, CA, is married with two adult children. I remember Leslie’s grandmother very well because she would answer the door when I went to their house and ask if Leslie could “come out and play.” I did not realize it nor understand it fully at the time, but we became best friends at the time, partly because the other kids on the block would not play with either of us (or were not allowed to play with either of us). She was of Japanese ancestry, and I was Black. For extra credit, read this page, view the two photos of Leslie, and make a comment at the bottom. Also, make any other observations beyond Korematu relating the case to the modern-day war on terror.

PolS 354. You should comment on the cases we have read regarding freedom of expression and assembly. Specifically, the fundamental constitutional rights of the crowd to assemble on public property and express themselves freely near my home.

PolS 358. You should comment on the cases we have read regarding fair housing, the 1969 Fair Housing Act, freedom of assembly, and any other constitutional issues raised in PolS 358.

PolS 359. To what extent does/can access to voting address the day-to-day experiences of marginalized groups? We moved into this house the same year as the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

According to the 1959 U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Chicago, IL, was the “most residentially segregated large city in the nation.” That was the year I was born.

I was born on the south side of Chicago before the 1964 Civil Rights Act and only four years after the Brown v Board Decree (1955). I learned about racial violence at an early age—when my parents purchased a new home in 1965. We were “blockbusters,” the first Black family on the block in 1965. I was in half-day kindergarten when my parents drove my sister and me to see our new house. It seemed huge. There was not one piece of furniture anywhere, and every wall in every room was freshly painted white. Painted white to conceal the damage done by the previous owners who moved away secretly in the middle of the night.

There was a fireplace and mantelpiece in the living room (a new vocabulary word for me) and a huge backyard where I would later pitch my tent and pretend to camp. It was much bigger than our apartment, where I had arrived five years earlier as a newborn and shared a room with my older sister. My sister and I ran through the house, pretending to get lost in the small rooms. I climbed inside the kitchen cabinets. There was also a basement, i.e., a secret laboratory, torture dungeon, pirate cave, and Big Wheel racecourse. And best of all, I would have my very own room. My own room where I would learn to read, count, play with G.I. Joe, my Hot Wheels racetrack, whittle my Pinewood Derby cars for cub scout merit badges, toss a ball in the air lying in the new bed, and stick chewed Bazooka Joe bubble gum under my

desk. Yes, my very own first desk and bookshelf that later became homework prison. And best of all, my older sister, with her long reddish hair and freckles, would have to stay out!

I still remember that first day, but also the first night after we moved into the house. We were the first “Negro” family on the block during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. A group of “white” neighbors threw a can of burning trash over our white picket fence and into our backyard that first night. Some were yelling, “Niggers go home,” “Go back to Africa,” and some threw rocks at our windows. Moreover, because my mother “looks white,” it may have also appeared that not only had a Negro family moved in the neighborhood, but possibly an interracial family! I understood none of this at the time. Why would people try to set our house on fire?

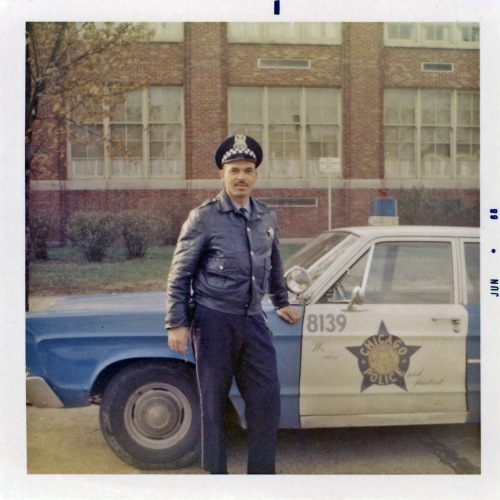

I remember my Dad (a WWII veteran), and my mother’s brother (a Korean War veteran), standing on the enclosed back porch that night. My Uncle was a young Chicago policeman, and I saw that he had his pistol in his hand and was shining a flashlight from the back porch into that vast dark yard and alley behind the house. He was using words I don’t think I had ever heard before. My Dad was also angry; why? I had never really seen him angry before. I heard my Mom say to my Dad and Uncle, “They’re going to burn us out.” I started walking to the porch, and my mother yelled at me to “get back” and “go to my room and stay there.” She said it really mean, like she would kill me if I did not get back. I think that scared me the most. I ran to my sister’s room. She was four years older, she was crying.

This violence went on for a while, to varying degrees, but never as bad as that first night. Sometimes, my Uncle’s police friends sat in their cars outside of our house. The white kids on the block were never allowed to play with me. My best friend for many years was Leslie Yokoyama, a Japanese American girl. Years later, I learned that her grandparents were in an internment camp during WWII. None of the white kids on the block played with her, either. We became inseparable.

The following summer, my Dad marched with thousands of others when Dr. King was stoned in Gage Park, Chicago, on August 5, 1966.

As a child, I always thought I was smart. Not because I necessarily earned excellent grades but because my parents kept telling me I was smart. It’s funny how kids believe what their parents tell them. I was formally educated in a Chicago Public elementary school, then a private middle school, a private high school, and then top-rated public universities for my BA and MA. I earned my Ph.D. at a

prestigious private university where I wore the armor of being the one token Black graduate student in the graduate program—next, a Stanford University post-doc. Most of my formal education, like the walls in our first new house, is freshly painted white. Painted white to conceal many truths.

My formal education prepared me for my long career in the academy—thirty-three-plus years as a professor. But I still struggle to unlearn the myths and lies I was taught (and even now, I sometimes teach). Integrating what I learned alone in university libraries with what I knew growing up on the South side of Chicago is increasingly irreconcilable.

Recent Comments